Adiabatic theorem

The adiabatic theorem is an important concept in quantum mechanics. Its original form, due to Max Born and Vladimir Fock (1928),[1] can be stated as follows:

- A physical system remains in its instantaneous eigenstate if a given perturbation is acting on it slowly enough and if there is a gap between the eigenvalue and the rest of the Hamiltonian's spectrum.

It may not be immediately clear from this formulation, but the adiabatic theorem is an extremely intuitive concept. Simply stated, a quantum mechanical system subjected to gradually changing external conditions can adapt its functional form, while in the case of rapidly varying conditions there is no time for the functional form of the state to adapt so the probability density remains unchanged.

The consequences of this apparently simple result are many, varied and extremely subtle. In order to make this clear we will begin with a fairly qualitative description, followed by a series of example systems, before undertaking a more rigorous analysis. Finally we will look at techniques used for adiabaticity calculations.

Contents |

Diabatic vs. adiabatic processes

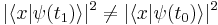

Diabatic process: Rapidly changing conditions prevent the system from adapting its configuration during the process, hence the probability density remains unchanged. Typically there is no eigenstate of the final Hamiltonian with the same functional form as the initial state. The system ends in a linear combination of states that sum to reproduce the initial probability density.

Adiabatic process: Gradually changing conditions allow the system to adapt its configuration, hence the probability density is modified by the process. If the system starts in an eigenstate of the initial Hamiltonian, it will end in the corresponding eigenstate of the final Hamiltonian.[2]

At some initial time  a quantum-mechanical system has an energy given by the Hamiltonian

a quantum-mechanical system has an energy given by the Hamiltonian  ; the system is in an eigenstate of

; the system is in an eigenstate of  labelled

labelled  . Changing conditions modify the Hamiltonian in a continuous manner, resulting in a final Hamiltonian

. Changing conditions modify the Hamiltonian in a continuous manner, resulting in a final Hamiltonian  at some later time

at some later time  . The system will evolve according to the Schrödinger equation, to reach a final state

. The system will evolve according to the Schrödinger equation, to reach a final state  . The adiabatic theorem states that the modification to the system depends critically on the time

. The adiabatic theorem states that the modification to the system depends critically on the time  during which the modification takes place.

during which the modification takes place.

For a truly adiabatic process we require  ; in this case the final state

; in this case the final state  will be an eigenstate of the final Hamiltonian

will be an eigenstate of the final Hamiltonian  , with a modified configuration:

, with a modified configuration:

.

.

The degree to which a given change approximates an adiabatic process depends on both the energy separation between  and adjacent states, and the ratio of the interval

and adjacent states, and the ratio of the interval  to the characteristic time-scale of the evolution of

to the characteristic time-scale of the evolution of  for a time-independent Hamiltonian,

for a time-independent Hamiltonian,  , where

, where  is the energy of

is the energy of  .

.

Conversely, in the limit  we have infinitely rapid, or diabatic passage; the configuration of the state remains unchanged:

we have infinitely rapid, or diabatic passage; the configuration of the state remains unchanged:

.

.

The so-called "gap condition" included in Born and Fock's original definition given above refers to a requirement that the spectrum of  is discrete and nondegenerate, such that there is no ambiguity in the ordering of the states (one can easily establish which eigenstate of

is discrete and nondegenerate, such that there is no ambiguity in the ordering of the states (one can easily establish which eigenstate of  corresponds to

corresponds to  ). In 1999 J. E. Avron and A. Elgart reformulated the adiabatic theorem, eliminating the gap condition.[3]

). In 1999 J. E. Avron and A. Elgart reformulated the adiabatic theorem, eliminating the gap condition.[3]

Note that the term "adiabatic" is traditionally used in thermodynamics to describe processes without the exchange of heat between system and environment (see adiabatic process). The quantum mechanical definition is closer to the thermodynamical concept of a quasistatic process, and has no direct relation with heat exchange.

Example systems

Simple pendulum

As an example, consider a pendulum oscillating in a vertical plane. If the support is moved, the mode of oscillation of the pendulum will change. If the support is moved sufficiently slowly, the motion of the pendulum relative to the support will remain unchanged. A gradual change in external conditions allows the system to adapt, such that it retains its initial character. This is referred to as an adiabatic process.[4]

Quantum harmonic oscillator

The classical nature of a pendulum precludes a full description of the effects of the adiabatic theorem. As a further example consider a quantum harmonic oscillator as the spring constant  is increased. Classically this is equivalent to increasing the stiffness of a spring; quantum-mechanically the effect is a narrowing of the potential-energy curve in the system Hamiltonian.

is increased. Classically this is equivalent to increasing the stiffness of a spring; quantum-mechanically the effect is a narrowing of the potential-energy curve in the system Hamiltonian.

If  is increased adiabatically

is increased adiabatically  then the system at time

then the system at time  will be in an instantaneous eigenstate

will be in an instantaneous eigenstate  of the current Hamiltonian

of the current Hamiltonian  , corresponding to the initial eigenstate of

, corresponding to the initial eigenstate of  . For the special case of a system like the quantum harmonic oscillator described by a single quantum number, this means the quantum number will remain unchanged. Figure 1 shows how a harmonic oscillator, initially in its ground state,

. For the special case of a system like the quantum harmonic oscillator described by a single quantum number, this means the quantum number will remain unchanged. Figure 1 shows how a harmonic oscillator, initially in its ground state,  , remains in the ground state as the potential-energy curve is compressed; the functional form of the state adapting to the slowly varying conditions.

, remains in the ground state as the potential-energy curve is compressed; the functional form of the state adapting to the slowly varying conditions.

For a rapidly increased spring constant, the system undergoes a diabatic process  in which the system has no time to adapt its functional form to the changing conditions. While the final state must look identical to the initial state

in which the system has no time to adapt its functional form to the changing conditions. While the final state must look identical to the initial state  for a process occurring over a vanishing time period, there is no eigenstate of the new Hamiltonian,

for a process occurring over a vanishing time period, there is no eigenstate of the new Hamiltonian,  , that resembles the initial state. The final state is composed of a linear superposition of many different eigenstates of

, that resembles the initial state. The final state is composed of a linear superposition of many different eigenstates of  which sum to reproduce the form of the initial state.

which sum to reproduce the form of the initial state.

Avoided curve crossing

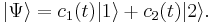

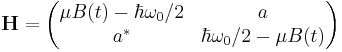

For a more widely applicable example, consider a 2-level atom subjected to an external magnetic field.[5] The states, labelled  and

and  using bra-ket notation, can be thought of as atomic angular-momentum states, each with a particular geometry. For reasons that will become clear these states will henceforth be referred to as the diabatic states. The system wavefunction can be represented as a linear combination of the diabatic states:

using bra-ket notation, can be thought of as atomic angular-momentum states, each with a particular geometry. For reasons that will become clear these states will henceforth be referred to as the diabatic states. The system wavefunction can be represented as a linear combination of the diabatic states:

With the field absent, the energetic separation of the diabatic states is equal to  ; the energy of state

; the energy of state  increases with increasing magnetic field (a low-field-seeking state), while the energy of state

increases with increasing magnetic field (a low-field-seeking state), while the energy of state  decreases with increasing magnetic field (a high-field-seeking state). Assuming the magnetic-field dependence is linear, the Hamiltonian matrix for the system with the field applied can be written

decreases with increasing magnetic field (a high-field-seeking state). Assuming the magnetic-field dependence is linear, the Hamiltonian matrix for the system with the field applied can be written

where  is the magnetic moment of the atom, assumed to be the same for the two diabatic states, and

is the magnetic moment of the atom, assumed to be the same for the two diabatic states, and  is some time-independent coupling between the two states. The diagonal elements are the energies of the diabatic states (

is some time-independent coupling between the two states. The diagonal elements are the energies of the diabatic states ( and

and  ), however, as

), however, as  is not a diagonal matrix, it is clear that these states are not eigenstates of the new Hamiltonian that includes the magnetic field contribution.

is not a diagonal matrix, it is clear that these states are not eigenstates of the new Hamiltonian that includes the magnetic field contribution.

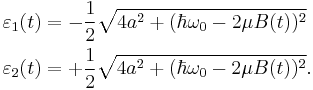

The eigenvectors of the matrix  are the eigenstates of the system, which we will label

are the eigenstates of the system, which we will label  and

and  , with corresponding eigenvalues

, with corresponding eigenvalues

It is important to realise that the eigenvalues  and

and  are the only allowed outputs for any individual measurement of the system energy, whereas the diabatic energies

are the only allowed outputs for any individual measurement of the system energy, whereas the diabatic energies  and

and  correspond to the expectation values for the energy of the system in the diabatic states

correspond to the expectation values for the energy of the system in the diabatic states  and

and  .

.

Figure 2 shows the dependence of the diabatic and adiabatic energies on the value of the magnetic field; note that for non-zero coupling the eigenvalues of the Hamiltonian cannot be degenerate, and thus we have an avoided crossing. If an atom is initially in state  in zero magnetic field (on the red curve, at the extreme left), an adiabatic increase in magnetic field

in zero magnetic field (on the red curve, at the extreme left), an adiabatic increase in magnetic field  will ensure the system remains in an eigenstate of the Hamiltonian

will ensure the system remains in an eigenstate of the Hamiltonian  throughout the process(follows the red curve). A diabatic increase in magnetic field

throughout the process(follows the red curve). A diabatic increase in magnetic field  will ensure the system follows the diabatic path (the solid black line), such that the system undergoes a transition to state

will ensure the system follows the diabatic path (the solid black line), such that the system undergoes a transition to state  . For finite magnetic field slew rates

. For finite magnetic field slew rates  there will be a finite probability of finding the system in either of the two eigenstates. See below for approaches to calculating these probabilities.

there will be a finite probability of finding the system in either of the two eigenstates. See below for approaches to calculating these probabilities.

These results are extremely important in atomic and molecular physics for control of the energy-state distribution in a population of atoms or molecules.

Proof of the Adiabatic theorem

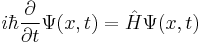

The first proof of this theorem was given by Max Born and Vladimir Fock, in Zeitschrift für Physik 51, 165 (1928). The concept of this theorem deals with the time-dependent Hamiltonian (which might be called a subject of Quantum dynamics) where the Hamiltonian changes with time.

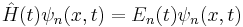

- For the case of time-independent Hamiltonian or in a broad sense time-independent potential (subjects of Quantum statics) the Schrödinger equation:

- can be simplified to the time-independent Schrödinger equation,

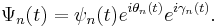

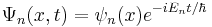

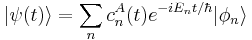

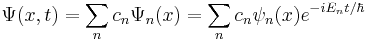

- as the general solution of the Schrödinger equation then can be found by the method of Separation of variables to give the wavefunction of the form:

- or, for nth eigenstate only :

- This signifies that a particle which starts from the nth eigenstate remains in the nth eigenstate, simply picking up a phase factor

.

.

In adiabatic process the Hamiltonian is time-dependent i.e, the Hamiltonian changes with time (not to be confused with Perturbation theory, as here the change in Hamiltonian is not small; it's huge, although it happens gradually). As because Hamiltonian changes with time, the eigenvalues and the eigenfunctions are time dependent.

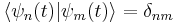

But at any particular instant of time the states still gives Complete orthogonal system. i.e,

Notice that: The dependence on position is tactically suppressed, as the time dependence part will be in more concern.  will considered to be the state of the system at time t no-matter how it depends on its position.

will considered to be the state of the system at time t no-matter how it depends on its position.

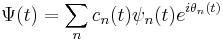

The general solution of time dependent Schrödinger equation now can be expressed as

where

where  .

.

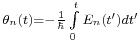

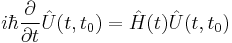

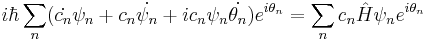

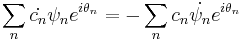

The phase  is called the dynamic phase factor. By substitution into the Schrödinger equation, another equation for the variation of the coefficients can be obtained

is called the dynamic phase factor. By substitution into the Schrödinger equation, another equation for the variation of the coefficients can be obtained

The term  gives

gives  and so the third term of left hand side cancels out with the right hand side leaving

and so the third term of left hand side cancels out with the right hand side leaving

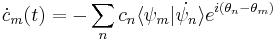

now taking the inner product with an arbitrary eigenfunction  , the on the left

, the on the left  gives

gives  which is 1 only for m = n otherwise vanishes. The remaining part gives

which is 1 only for m = n otherwise vanishes. The remaining part gives

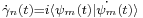

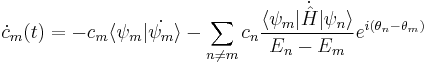

calculating the expression for  from differentiating the modified time independent Schrödinger equation above it can have the form

from differentiating the modified time independent Schrödinger equation above it can have the form

This is also exact.

For the adiabatic approximation which says the time derivative of Hamiltonian i.e,  is extremely small as time is largely taken, the last term will dropout and one has

is extremely small as time is largely taken, the last term will dropout and one has

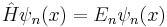

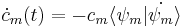

that gives, after solving,

having defined the geometric phase as  . Putting it in the expression for nth eigenstate one has

. Putting it in the expression for nth eigenstate one has

So, for an adiabatic process, a particle starting from nth eigenstate also remains in that nth eigenstate like it does for the time-independent processes, only picking up a couple of phase factors. The new phase factor  can be canceled out by an appropriate choice of gauge for the eigenfunctions. However, if the adiabatic evolution is cyclic, then

can be canceled out by an appropriate choice of gauge for the eigenfunctions. However, if the adiabatic evolution is cyclic, then  becomes a gauge-invariant physical quantity, known as the Berry phase.

becomes a gauge-invariant physical quantity, known as the Berry phase.

Deriving conditions for diabatic vs adiabatic passage

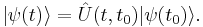

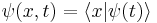

We will now pursue a more rigorous analysis.[6] Making use of bra-ket notation, the state vector of the system at time  can be written

can be written

,

,

where the spatial wavefunction alluded to earlier is the projection of the state vector onto the eigenstates of the position operator

.

.

It is instructive to examine the limiting cases, in which  is very large (adiabatic, or gradual change) and very small (diabatic, or sudden change).

is very large (adiabatic, or gradual change) and very small (diabatic, or sudden change).

Consider a system Hamiltonian undergoing continuous change from an initial value  , at time

, at time  , to a final value

, to a final value  , at time

, at time  , where

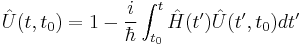

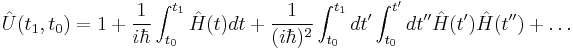

, where  . The evolution of the system can be described in the Schrödinger picture by the time-evolution operator, defined by the integral equation

. The evolution of the system can be described in the Schrödinger picture by the time-evolution operator, defined by the integral equation

,

,

which is equivalent to the Schrödinger equation.

,

,

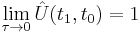

along with the initial condition  . Given knowledge of the system wave function at

. Given knowledge of the system wave function at  , the evolution of the system up to a later time

, the evolution of the system up to a later time  can be obtained using

can be obtained using

The problem of determining the adiabaticity of a given process is equivalent to establishing the dependence of  on

on  .

.

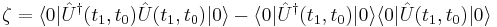

To determine the validity of the adiabatic approximation for a given process, one can calculate the probability of finding the system in a state other than that in which it started. Using bra-ket notation and using the definition  , we have:

, we have:

.

.

We can expand

.

.

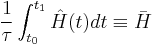

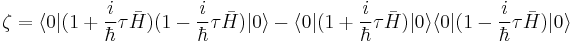

In the perturbative limit we can take just the first two terms and substitute them into our equation for  , recognizing that

, recognizing that

is the system Hamiltonian, averaged over the interval  , we have:

, we have:

.

.

After expanding the products and making the appropriate cancellations, we are left with:

,

,

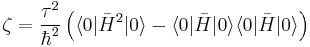

giving

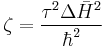

,

,

where  is the root mean square deviation of the system Hamiltonian averaged over the interval of interest.

is the root mean square deviation of the system Hamiltonian averaged over the interval of interest.

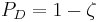

The sudden approximation is valid when  (the probability of finding the system in a state other than that in which is started approaches zero), thus the validity condition is given by

(the probability of finding the system in a state other than that in which is started approaches zero), thus the validity condition is given by

,

,

which is a statement of the time-energy form of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle.

Diabatic passage

In the limit  we have infinitely rapid, or diabatic passage:

we have infinitely rapid, or diabatic passage:

.

.

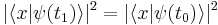

The functional form of the system remains unchanged:

.

.

This is sometimes referred to as the sudden approximation. The validity of the approximation for a given process can be characterized by the probability that the state of the system remains unchanged:

.

.

Adiabatic passage

In the limit  we have infinitely slow, or adiabatic passage. The system evolves, adapting its form to the changing conditions,

we have infinitely slow, or adiabatic passage. The system evolves, adapting its form to the changing conditions,

.

.

If the system is initially in an eigenstate of  , after a period

, after a period  it will have passed into the corresponding eigenstate of

it will have passed into the corresponding eigenstate of  .

.

This is referred to as the adiabatic approximation. The validity of the approximation for a given process can be determined from the probability that the final state of the system is different from the initial state:

.

.

Calculating diabatic passage probabilities

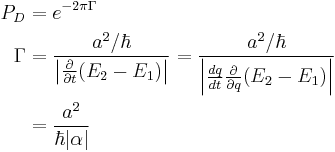

The Landau-Zener formula

In 1932 an analytic solution to the problem of calculating adiabatic transition probabilities was published separately by Lev Landau and Clarence Zener,[7] for the special case of a linearly changing perturbation in which the time-varying component does not couple the relevant states (hence the coupling in the diabatic Hamiltonian matrix is independent of time).

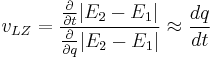

The key figure of merit in this approach is the Landau-Zener velocity:

,

,

where  is the perturbation variable (electric or magnetic field, molecular bond-length, or any other perturbation to the system), and

is the perturbation variable (electric or magnetic field, molecular bond-length, or any other perturbation to the system), and  and

and  are the energies of the two diabatic (crossing) states. A large

are the energies of the two diabatic (crossing) states. A large  results in a large diabatic transition probability and vice versa.

results in a large diabatic transition probability and vice versa.

Using the Landau-Zener formula the probability,  , of a diabatic transition is given by

, of a diabatic transition is given by

The numerical approach

For a transition involving a nonlinear change in perturbation variable or time-dependent coupling between the diabatic states, the equations of motion for the system dynamics cannot be solved analytically. The diabatic transition probability can still be obtained using one of the wide variety of numerical solution algorithms for ordinary differential equations.

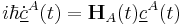

The equations to be solved can be obtained from the time-dependent Schrödinger equation:

,

,

where  is a vector containing the adiabatic state amplitudes,

is a vector containing the adiabatic state amplitudes,  is the time-dependent adiabatic Hamiltonian,[5] and the overdot represents a time-derivative.

is the time-dependent adiabatic Hamiltonian,[5] and the overdot represents a time-derivative.

Comparison of the initial conditions used with the values of the state amplitudes following the transition can yield the diabatic transition probability. In particular, for a two-state system:

for a system that began with  .

.

See also

- Landau–Zener formula

- Berry phase

- Quantum stirring, ratchets, and pumping

- Born–Oppenheimer approximation

References

- ^ M. Born and V. A. Fock (1928). "Beweis des Adiabatensatzes". Zeitschrift für Physik A 51 (3–4): 165–180. doi:10.1007/BF01343193.

- ^ T. Kato (1950). "On the Adiabatic Theorem of Quantum Mechanics". Journal of the Physical Society of Japan 5 (6): 435–439. Bibcode 1950JPSJ....5..435K. doi:10.1143/JPSJ.5.435.

- ^ J. E. Avron and A. Elgart (1999). "Adiabatic Theorem without a Gap Condition" (PDF). Communications in Mathematical Physics 203 (2): 445–463. arXiv:math-ph/9805022. Bibcode 1999CMaPh.203..445A. doi:10.1007/s002200050620. http://www.springerlink.com/content/ad0jyug24jg97nt6/fulltext.pdf.

- ^ Griffiths, David J. (2005). "10". Introduction to Quantum Mechanics. Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-111892-7.

- ^ a b S. Stenholm (1994). "Quantum Dynamics of Simple Systems". The 44th Scottish Universities Summer School in Physics: 267–313.

- ^ Messiah, Albert (1999). "XVII". Quantum Mechanics. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-40924-4.

- ^ C. Zener (1932). "Non-adiabatic Crossing of Energy Levels". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series A 137 (6): 692–702. Bibcode 1932RSPSA.137..696Z. doi:10.1098/rspa.1932.0165. JSTOR 96038.

![c_m(t) = c_m(0)\exp[-\textstyle\int\limits_{0}^{t}\langle\psi_m(t')|\dot{\psi_m}(t')\rangle dt'] = c_m(0)e^{i\gamma_m(t)},](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/442e90414a7a0f9da3c1202acc7f6829.png)